For years, I’ve avoided Ian McEwan’s novel, Machines Like Me, partly out of ambivalence about other McEwan novels I’d read, but mainly in response to an interview in The Guardian, where McEwan was quoted as saying, ‘There could be an opening … for novelists to explore this future, not in terms of travelling at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots, but in actually looking at the human dilemmas of being close up to something that you know to be artificial but which thinks like you.’

To anyone engaged with science fiction’s rich tradition of exploring ethical and societal dilemmas, comments like these read as wilfully ignorant and snobbish.

Lately, however, I’ve been asking myself – do I really want to be the blogger who avoids reading an on-theme book just because of a quote that may (may) have been taken out of context? No, I do not want to be that blogger.

And so, I borrowed Machines Like Me from my local library, and I read it from cover to cover. Here’s what I made of it––

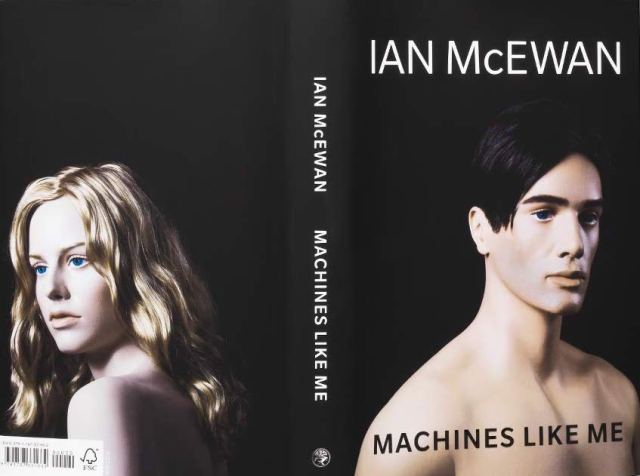

Set in an alternate 1982 UK, Machines Like Me is described in its blurb as being about a love triangle between a man, a woman and an artificial human – and about a profound moral dilemma.

Sounds promising.

The story is narrated by Charlie, an existentially lost, 30-something who likes the sound of his own voice and has recently come into a large sum of money. Charlie blows most of his cash – 86,000 pounds worth – on buying Adam, one of the first 25 ‘artificial humans’ made available for private purchase. Charlie justifies his buy, grandiosely, as an important experiment – and moves straight on to using Adam as a tool to seduce upstairs-neighbour Miranda.

Miranda is a 22-year-old, ‘mature for her years’ PhD student, who readily falls into Charlie’s bed and straight into a relationship with Charlie. This match is not made in heaven. One evening, after a moderately heated argument about politics, Miranda spends the night – one night – having revenge sex (ergh) with android Adam. A sordid fall-out ensues, complicated by Adam’s AI-informed knowledge of Miranda’s mysterious past. The moral dilemma promised in the blurb is experienced most acutely by Adam. His response is violent and destructive, yet it also has a staged thought-experiment quality that, for me, dulls the impact of the story’s climax. By the end of the novel, everyone has behaved badly, except Alan Turing, who, in this alternate history, is alive and well at 70 years old, happily settled in a committed same-sex relationship.

Much of the drama in Machines Like Me hinges on Miranda’s sensationalistic backstory, a backstory that includes [spoiler] a man imprisoned for a rape he didn’t commit. McEwan certainly isn’t deliberately saying ‘all women are liars’ here (or at least, I don’t think he is), but I am uncomfortable with how this plot point feeds into misogynistic myths about rape. Add to this the two-dimensionality of Miranda’s characterisation, the lack of believable passion in the promised love triangle, and the tedium of Charlie’s detached, pontificating narration, and my overall experience of reading this book was ‘meh’.

There is much more I could say about Machines Like Me – good as well as bad – however, for Electric Baa purposes, my focus is this: does this book rise to the challenge that McEwan threw down in the Guardian interview? Did this book actually get me thinking about ‘the human dilemmas of being close up to something that you know to be artificial but which thinks like you’?

There is a scene, part way into the book, where Miranda’s father mistakes Charlie for Adam, and vice versa. I guess McEwan’s intent here is to problematise the nature of human versus artificial intelligence. For me, however, the scene falls flat. Charlie, Adam and Miranda’s father all think and act like 70-something white educated males. How they experience the world, how they process and convey their experience, is not relatable to me, or even particularly interesting to me. McEwan’s bias is writ large, unquestioned and problematic. The huge irony here is that AI bias is shaping up to be one of the more serious negative impacts of our rampant AI adoption. Hmm.

It’s possible I’ve misread Machines Like Me. After all, when the book was released, many reviewers were impressed by it. If you are already a McEwan fan, you’ll no doubt love Machines Like Me for its style and for its pointed cleverness (it has plenty of that). If you’re not a McEwan fan, and you’re looking for AI-themed reads that are engaging, thought provoking and relevant to our times, you might prefer to seek out stories that loudly and proudly brand themselves as science fiction, or futuristic fiction – even if they feature travel at 10 times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots.

Have you read Machines Like Me? Am I being too harsh about what McEwan does – or doesn’t do – in this book?